A Line Which Forms a Volume is an annual critical reader of graphic design-led research that is authored, edited, designed and made public by MA Graphic Media Design participants at London College of Communication, UAL.

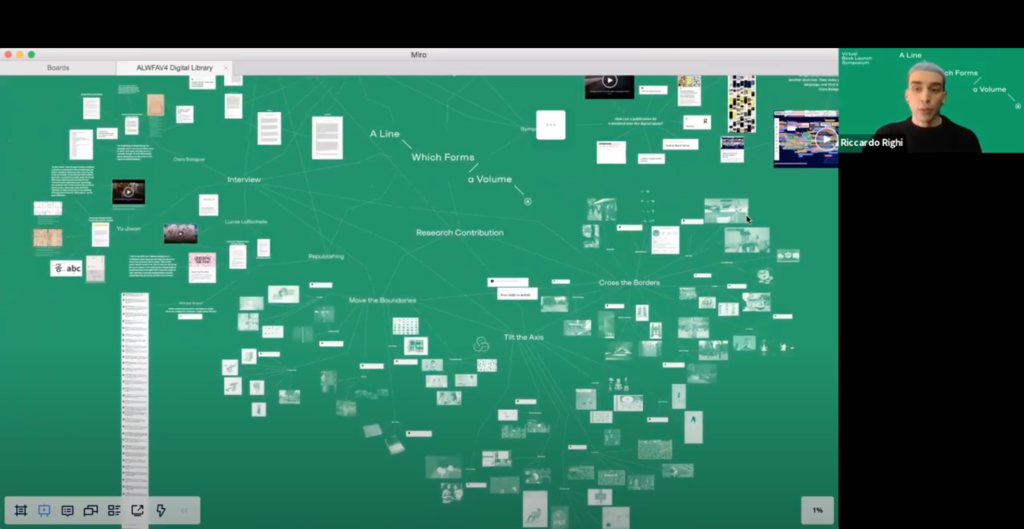

A Line of critical inquiry is a multi-directional thread with a life of its own. It shifts, spins, stretches, splices; simultaneously, in parallel, and apart. It is constantly reshaping and reformulating itself in response to the accelerating context in which graphic design exists. A Volume is both a tangible object and an audible moment in time. A Line joins together many research narratives. It should be read continuously not as sporadic works. A Volume is a space that projects, amplifies, and disseminates. A Line is a question, a conversation, a response. A Volume is the beginning of a collective design enquiry. It is an opportunity to share research in a wider context of design criticism and publishing. A Line feeds a relay process: the design informs the editorial approach, and vice versa. A Line Which Forms a Volume is a publication and symposium of design research from London College of Communication that brings together narrative, messages and meanings.

The concept for A Line Which Forms a Volume belongs to the French novelist and essayist, Michel Butor. ‘Listen to someone making a speech’, Butor wrote in his essay ‘The Book as Object’, ‘every word follows one other, precedes one other. As a result, they take their places along a line activated by a meaning, along an axis.’ The best way to store such a line—‘such a “thread”’—he states is to ‘roll it up’. By definition we know that a ‘volume’—from the Latin, volvere—means ‘to roll’, because that was the way written matter was once stored. But there is also volume in the sense of an occupied or enclosed space, and in the quantity or power of sound. This publication lays claim to all of these definitions.

We intend for this research to be public— voluble—and to resonate. As a record, this publication tracks the reeling of ideas between texts, splicing them together with graphic devices and conceptual links to form a continuous line. ‘Writing’s first advantage, as we all know, is that it enables language to last’, explains Butor, ‘leaving accessible to our eyes what our ears would already have missed’. A Line Which Forms a Volume has formed and filled a space for MA Graphic Media Design research at London College of Communication. This is the first issue but not the last. The editorial team, designers and the group of participants who contribute to each issue will roll-over, gain momentum and continue with lines of inquiry, narrative threads, or any other metaphorical unravelling of graphic design research that they choose.

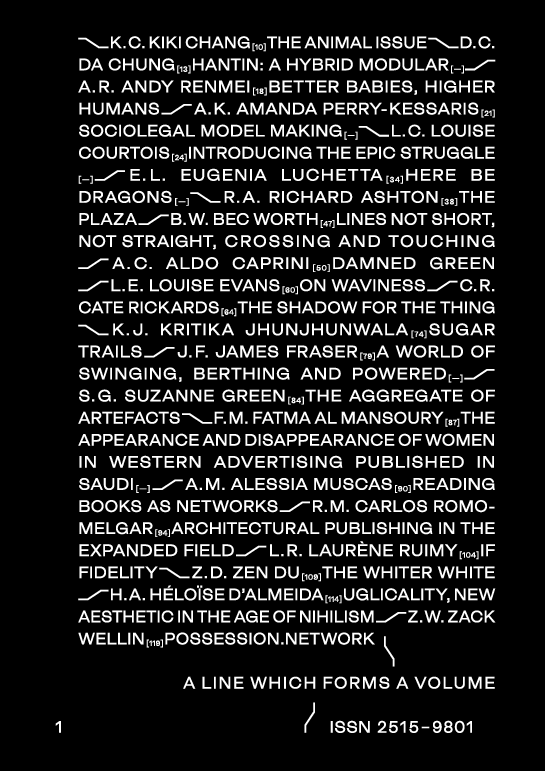

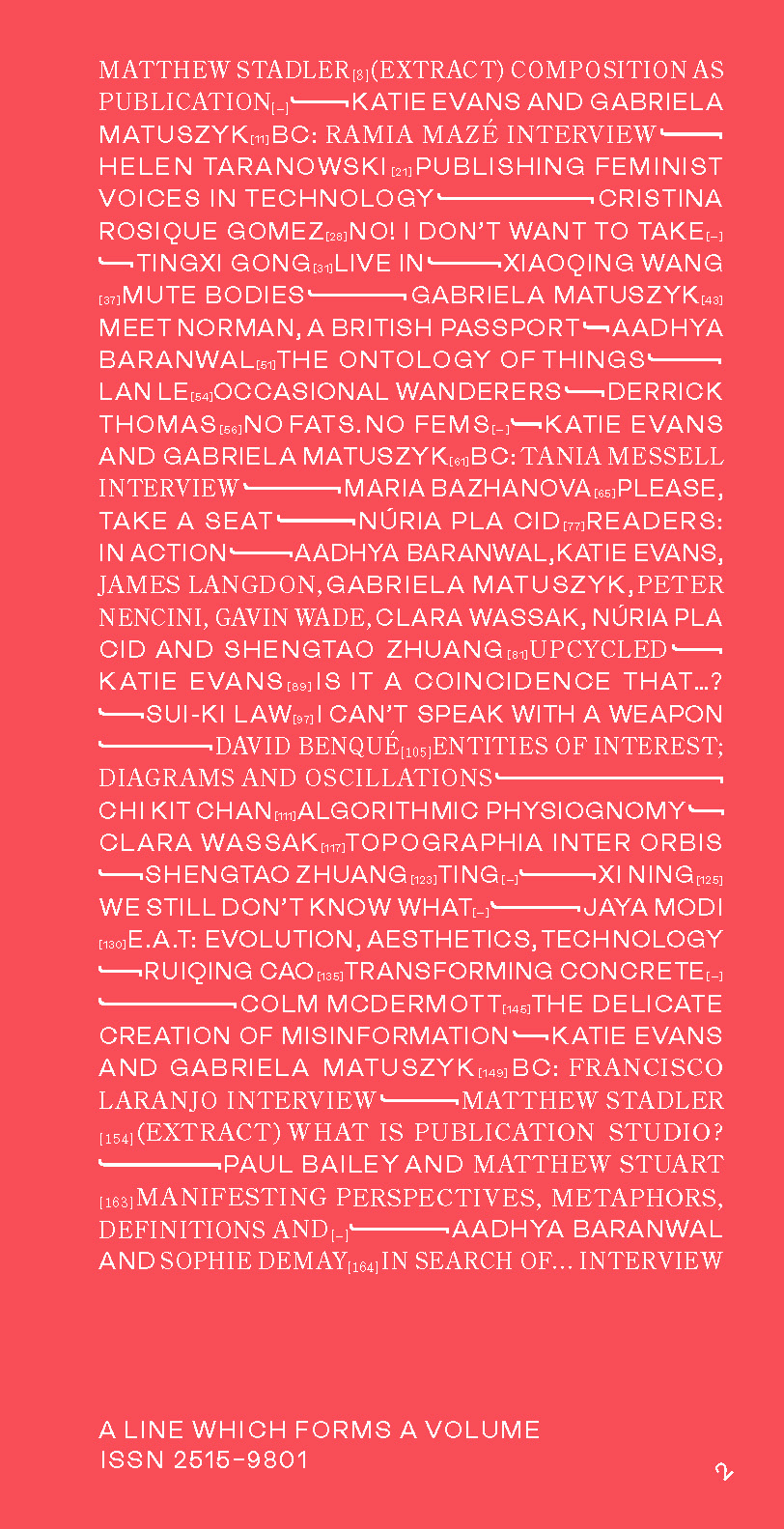

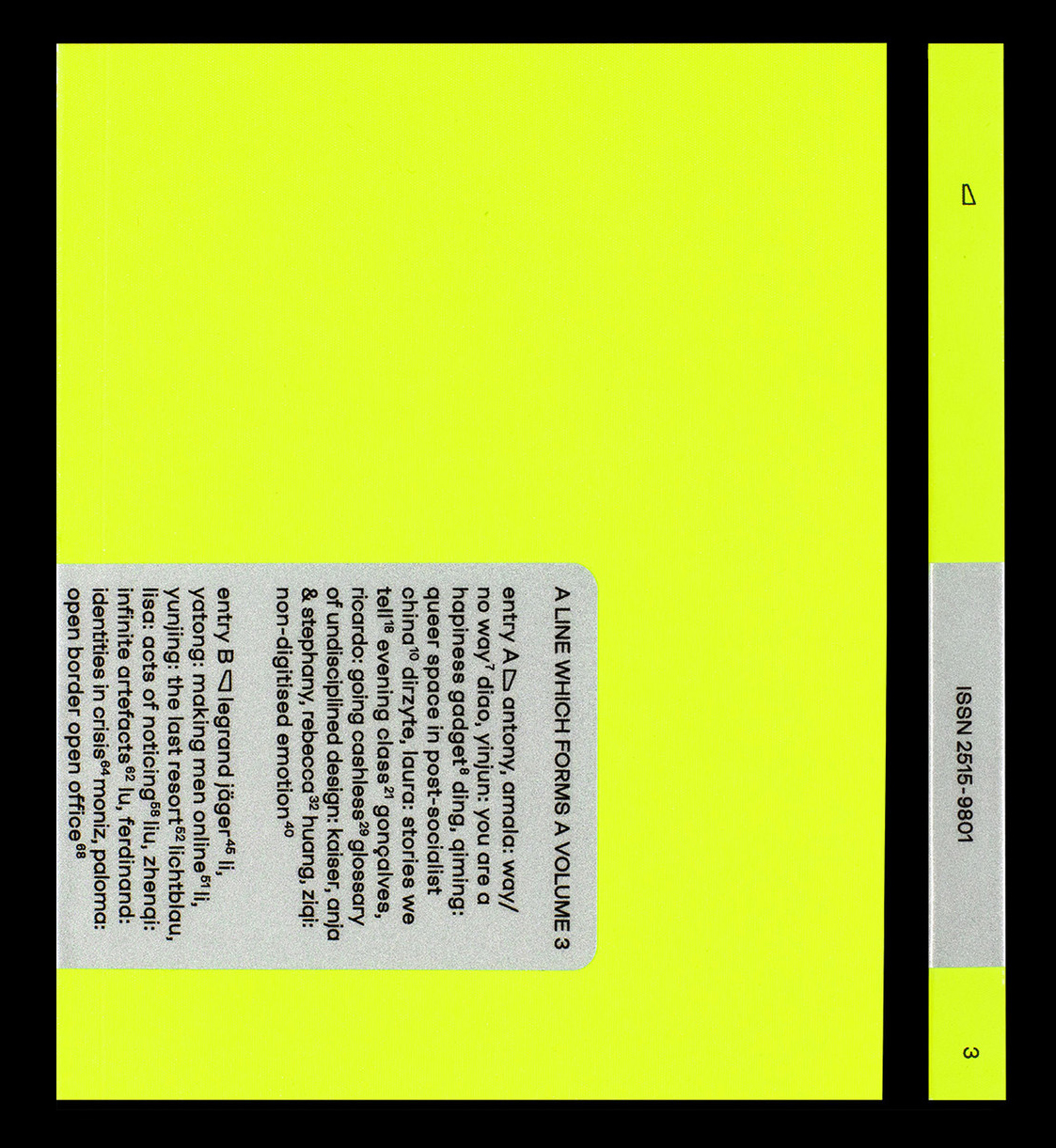

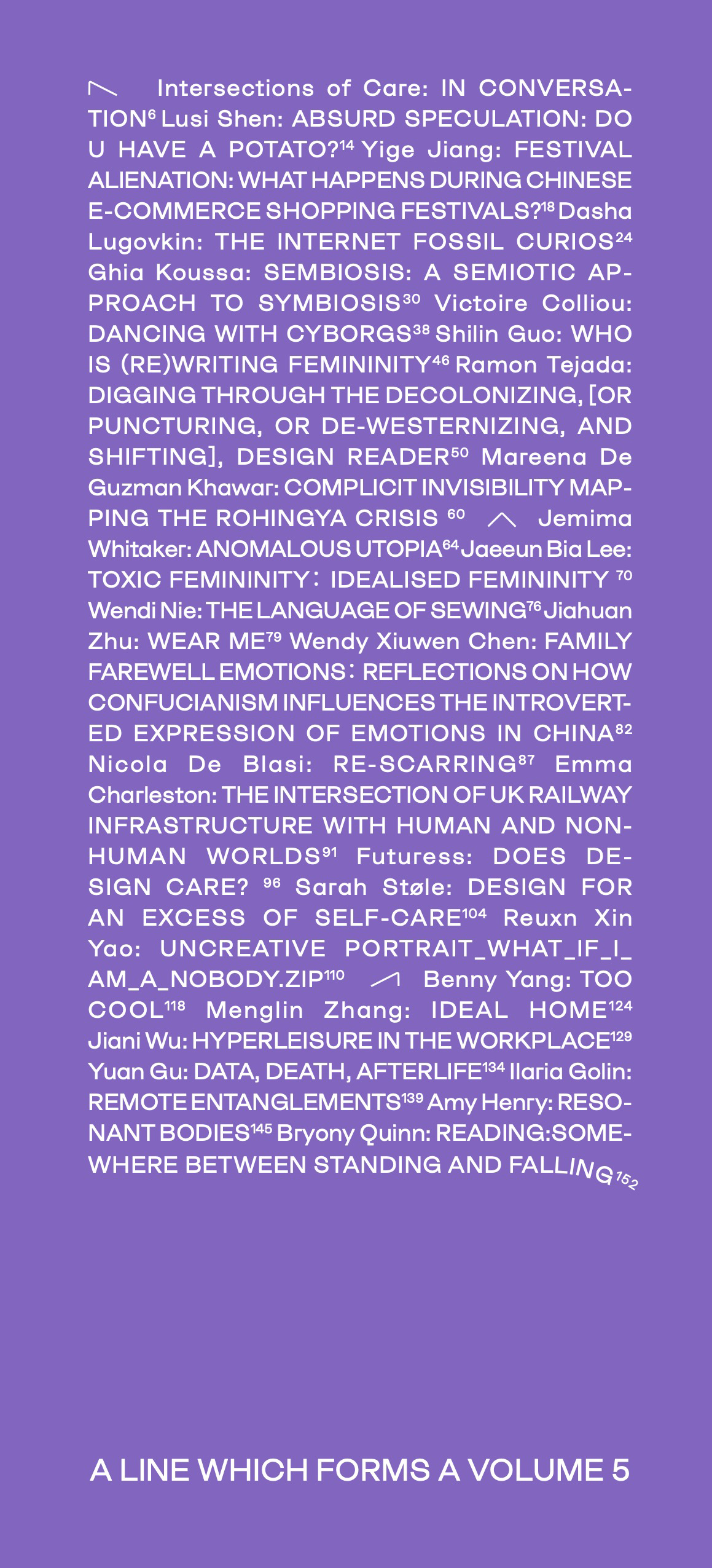

CONTRIBUTORS (in order of appearance)

Kiki Chang, Da Chung, Andy Renmei, Amanda Perry-Kessaris, Louise Courtois, Eugenia Luchetta, Richard Ashton, Bec Worth, Aldo Caprini, Louise Evans, Cate Rickards, Kritika Jhunjhunwala, James Fraser, Suzanne Green, Fatma Al Mansoury, Alessia Muscas, Carlos Romo-Melgar, Laurène Ruimy, Zen Du, Héloïse d’Almeida, Zack Wellin, Stuart Bertolotti-Bailey, Eleanor Vonne Brown, Jack Self, Wayne Daly and Claire Lyon.

STOCKISTS

Currently out of stock.

COLOPHON

Designers

Aldo Caprini

Carlos Romo-Melgar

Editors

Katie Evans

Gabriela Matuszyk

Production Manager

Clare Larsen–Burnett

Editorial team

Héloïse d’Almeida

Zen Du

Louise Evans

Kritika Jhunjhunwala

Cate Rickards

Laurène Ruimy

Zack Wellin

Symposium organisers

Richard Ashton

Bec Worth

Archivist

Cate Rickards

Design Advisors

Wayne Daly

Claire Lyon

Editorial Advisor

Bryony Quinn

Kindly supported by

The Student Engagement and Experience Fund, London College of Communication

ISSN: 2515-9801